Hey folks! Rad here. Today we are tackling the scariest beast in the IT jungle: The Legacy Monolith.

You know the one. It's that 10-year-old Java application running on a cluster of massive VMs that nobody wants to touch. It's got business logic spaghetti-coded so tight that fixing a typo in the "About Us" page somehow breaks the checkout process.

I've seen too many startups and enterprises try the "Big Bang" rewrite. You know, where they say, "We're going to freeze features for six months, rewrite everything in Go/Kubernetes, and then flip the switch!"

Spoiler alert: That never works. It turns into two years, the market moves on, and on launch day, the new system crashes harder than my diet on Thanksgiving.

There is a better way. It's called the Strangler Fig Pattern. And today, I'm going to show you how to pull it off using Google Cloud Load Balancing (GCLB).

What is the Strangler Fig?

The name comes from a type of fig tree that grows around a host tree. It starts small, wrapping its roots around the host, and eventually, the original tree dies and rots away, leaving just the fig in its place.

In cloud terms:

- The Host Tree: Your dusty old Monolith.

- The Fig: Your shiny new Microservices.

- The Goal: Slowly replace functionality piece by piece until the Monolith is gone (or small enough to ignore).

The secret sauce to making this work without the user noticing? Intelligent Traffic Routing.

The Architecture: The Load Balancer as the Traffic Cop

In August 2021, the Google Cloud Global External HTTP(S) Load Balancer is, frankly, a masterpiece. It's not just for scaling; it's your migration tool.

Here is the high-level plan. We aren't touching the Monolith's code yet. We are putting a layer in front of it.

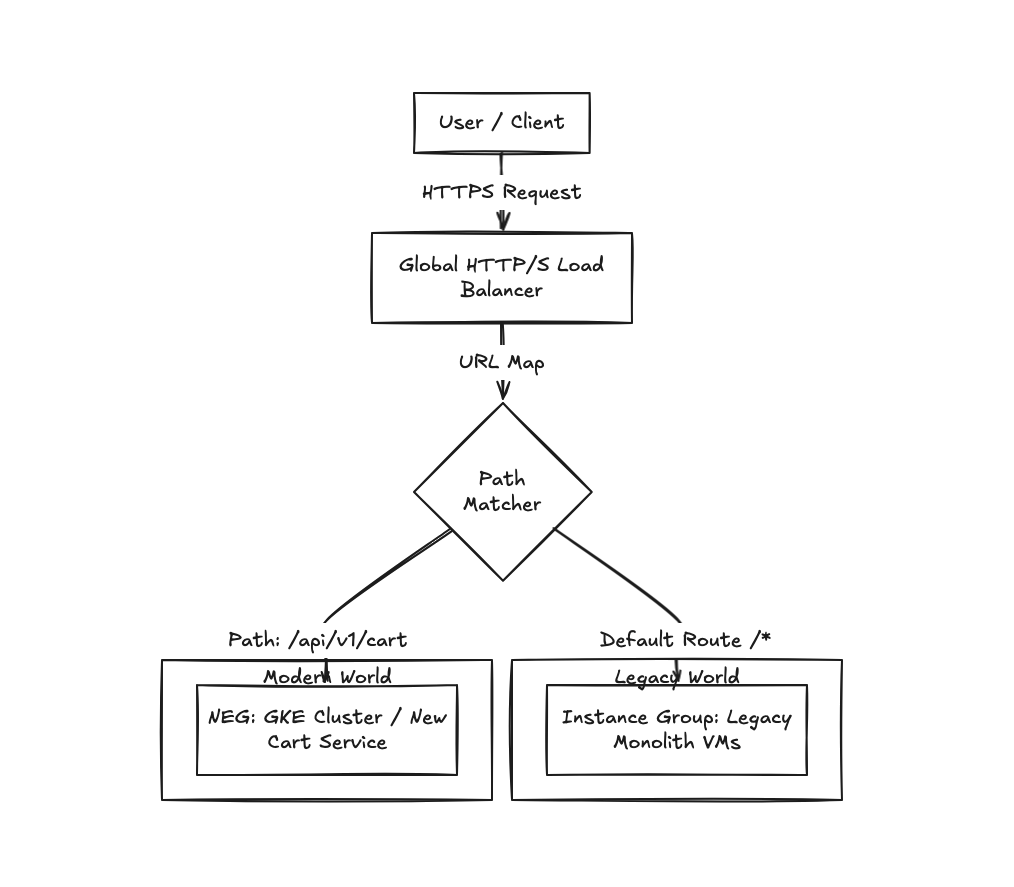

The Diagram

Here is what we are building:

What's happening here?

- The Front Door: All traffic hits the GCLB Anycast IP.

- The Brain (URL Map): This is where the magic happens. We define rules.

- Does the URL start with

/api/v1/cart? Send it to the new Kubernetes cluster (via a Network Endpoint Group, or NEG). - Everything else? Send it to the old Instance Group running the Monolith.

- Does the URL start with

Step-by-Step Implementation

Let's say we are migrating the "Cart" functionality of our e-commerce app.

1. Stand up the New Service

We build the "Cart" service as a microservice. Maybe it's a Spring Boot app containerized on GKE (Google Kubernetes Engine), or maybe it's Python on Cloud Run. Let's assume GKE for this project.

We deploy it, expose it internally, and make sure it works in isolation.

2. Configure the Backend Services

In GCP Console (or Terraform, if you're behaving), you need two Backend Services:

- Backend A (Legacy): Points to your Managed Instance Group (MIG) containing the VM monoliths.

- Backend B (Modern): Points to the GKE NEG (Network Endpoint Group) for the Cart service.

Rad's Tip: If you haven't switched to NEGs for container-native load balancing yet, do it. It skips the kube-proxy hop and sends traffic directly to the Pod IP. Lower latency, happier users.

3. The "Strangler" Move: Updating the URL Map

This is the moment of truth. You modify the Host and Path rules in the Load Balancer.

You aren't changing DNS. You aren't asking users to go to new-app.company.com. You are simply telling the Load Balancer:

"Hey, if you see a request for

/cartor/checkout, don't bother the old monolith. Send that to the new guys in Backend B."

The users have no idea. One minute they are browsing products (Monolith), the next they are adding to cart (Microservice). It's seamless.

Why Google Cloud Load Balancing specifically?

You might ask, "Rad, can't I just use Nginx or HAProxy for this?"

Sure, you can. But here's why I prefer GCLB for this pattern:

- Global Anycast IP: You get one IP address for the whole world. No matter how messy your backend migration gets, the frontend entry point never changes.

- Serverless NEGs: If you decide your new microservice should be on Cloud Run (Serverless), GCLB integrates natively. You can mix and match VMs, Containers, and Serverless functions behind the same load balancer URL. That is huge.

- Risk Mitigation: If the new Cart service explodes (it happens), you can revert the URL Map change in seconds. Traffic flows back to the Monolith. It's a gigantic "Undo" button for your architecture.

The "Gotchas" (Because Experience is Pain)

I promised to keep it real. Here is where I've face-planted in the past, so you don't have to.

1. The "Sticky Session" Nightmare

Your Monolith probably uses JSESSIONID or some in-memory session state. The user logs in, the Monolith remembers them on that specific server.

Your new Microservice is likely stateless (using JWTs or Redis).

The Trap: A user logs in on the Monolith. They click "Cart" and go to the Microservice. The Microservice says, "Who are you? I don't know this Session ID."

The Fix: You need a shared session store (like Cloud Memorystore for Redis) or migrate to token-based auth (OIDC/JWT) before you start strangling.

2. The Database Tangle

Just because you split the code doesn't mean you split the data. The Trap: The new Cart microservice is still connecting to the same massive Oracle/MySQL DB as the Monolith. The Fix: This is okay for Day 1, but it's an anti-pattern long term. The Monolith might lock tables that the Microservice needs. Eventually, you need to migrate the data too, but that's a topic for another post.

3. Path Rewrites

The Trap: The Monolith expects /app/cart. Your new service expects just /.

The Fix: GCLB allows for URL rewriting. Make sure you strip the prefix if your container isn't expecting it, or you'll get a lot of 404s.

Wrap Up

The Strangler Fig pattern isn't just about code; it's about risk management. By using Google Cloud Load Balancing to slice off traffic by path, you turn a terrifying "Big Bang" migration into a series of boring, manageable updates.

And in the world of Ops, "boring" is the highest compliment you can get.

Coming up next: Now that we know how to route the traffic, we need to talk about the build process. In Part 2, I'm going to share why we ditched heavy Dockerfiles and switched to Jib and Cloud Build to containerize our Java legacy apps without losing our minds.

Stay tuned, and keep your load balancers warm!

-Rad